On May 29, 1945, a 22-year-old soldier wrote a letter home to his parents in Indianapolis, Indiana. In that letter, he described being captured by a German panzer division in what is now called the Battle of the Bulge. It was Germany’s Hail Mary with 450,000 soldiers and 1,500 tanks storming parts of Belgium and France to try to win the war that they were losing.

Once captured, the American soldier and his unit were loaded on to unheated box cars for a ten-day train ride to a prisoner of war camp south of Dresden. After five months watching fellow prisoners die from starvation, abuse, and Allied air raids, the soldier and eight others stole a German truck and drove for eight days until they reached Soviet territory.

It was time to go home.

When he got there, he married his high school sweetheart, Jane Marie, and they moved west to enroll in the University of Chicago. Likely influenced by the human extremes that he witnessed during the war, he signed up for a joint undergraduate/graduate program in anthropology. After a few years in the program, he wrote a master’s thesis that he called, “The Fluctuations Between Good and Evil in Simple Tales.” And it had just one main idea.

All stories have shapes, and the great ones look alike.

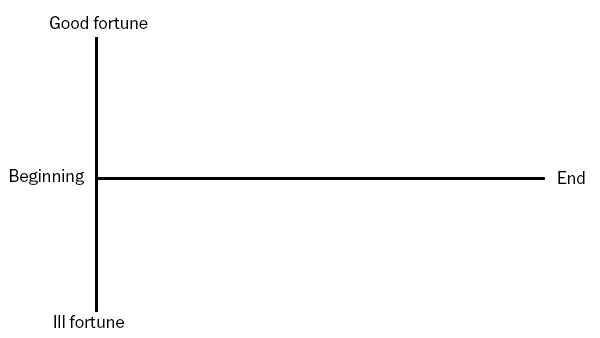

This might sound complicated, but it’s really not that bad. The idea is that if you create a graph where the horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis represents the fortune of the main character, you can actually map every story ever told.

And when that anthropology student started doing this, he saw that the greatest stories had similar shapes. For example, Cinderella and the New Testament are roughly identical (as shown below in the graphic created by Maya Eilam).

This felt like a big deal. So, the student finished his thesis and excitedly presented it to the faculty at the university. Unfortunately, his committee did not agree. They rejected the thesis on the basis that it was not actually anthropology at all. With no money and a small child to support, he had no other choice than to walk away without a degree. He called his brother who worked at General Electric, and got a job writing in the PR department.

His name was Kurt Vonnegut, and that’s when he started writing stories.

Vonnegut would go on to become one of the most famous authors in American history. And it was his rejected thesis that helped him do it. Because whether it was Cat’s Cradle, Slaughterhouse-Five, Player Piano, or any of the others that Vonnegut wrote, he carefully mapped the shape of every story that he ever told. And he made sure that his stories resembled the best (he explains how it’s done in this video).

This is also Hollywood’s greatest secret. So, it’s no accident that the first four Rocky movies all have the same shape: 1) Rocky finds some initial success; 2) tragedy strikes and he faces a seemingly impossible task; 3) Rocky works and trains harder than any human ever could; and 4) Rocky wins the fight. It’s the Cinderella story: rise then fall then rise again.

Which brings us to our main point.

There are really just six good stories in the world today.

Researchers from the University of Vermont and the University of Adelaide used artificial intelligence to digitally map over 2,000 works of fiction. Their first finding was that the great stories have similar shapes. That is, they validated Vonnegut’s thesis. Their second finding was that there are just six main story arcs:

Rags to Riches (rise)

Riches to Rags (fall)

Man in a Hole (fall then rise)

Icarus (rise then fall)

Cinderella (rise then fall then rise)

Oedipus (fall then rise then fall)

But what does all of this have to do with us?

Just like Vonnegut and those Hollywood screenwriters, we can shape the stories that we tell. And we can make ours look just like the best. It’s the trick that we use to write these articles (thank you for reading, by the way), and you can do it too. Whether it’s a pitch for a new idea, a presentation to the board, the launch of a new strategy, or an email announcing the company picnic, you can bring your message to life by deliberately shaping the story you tell. And understanding these six main story arcs is the only place to start.

Which brings us back to that letter that Kurt Vonnegut wrote his parents in 1945. He couldn’t have known then that he would become one of the world’s most famous authors. Nor could he have known that he would change the way that we see story. But he did end his letter with this prophetic statement: “I've too damned much to say, the rest will have to wait.”

Luckily for us, he found out just how to say it. And now we can too.

Your story awaits.

***********