Joe Rantz was 10 years old when his family left him. It was 1924. His father had remarried after Joe’s mother died seven years earlier, and for no obvious reason his stepmother Thula just couldn’t stand him. So, Joe walked the dirt roads of Seqium, Washington looking for a place to live. He eventually discovered that the schoolhouse door didn’t lock and started sleeping there. Joe stayed in school and foraged for food by fishing, hunting, and working odd jobs.

Eventually, his father did insist that Joe be allowed to return to live with the family, but that didn’t last long. When Joe was 15 years old, he came home from school to find his dad, stepmom, and four younger siblings driving away. They wouldn’t tell him where they were going. Joe was alone, and this time it was for good. He spent the next two years living in a half-finished cabin in the woods, surviving by logging timber, clearing tree stumps, baling hay, and building fences.

But this is not just another hard knocks Great Depression story.

Joe’s oldest brother and his wife ended up inviting him to live with them in Seattle for his senior year. Joe enrolled in Roosevelt High School, and with the extra time that he now had, he thrived in his studies and took up sports. One day in gymnastics practice, Joe was doing a routine on the high bar when a man named Al Ulbrickson walked in. Ulbrickson was the University of Washington rowing coach, and when he saw Joe’s muscular build, he approached him and encouraged Joe to try out for his crew team.

There were no scholarships for college sports in those days, so Joe knew that if he wanted to go to Washington, he would have to pay his own way. After graduating, Joe worked for 15 months on two Works Project Administration jobs. The first was manually digging and paving highways and the second was rappelling down cliffs to clear rock for the Grand Coulee Dam. He averaged 60 hours a week.

So began the rise of the Boys of ‘36.

Joe made the freshmen rowing team when he enrolled in the University of Washington in 1934. And by studying hard and rowing harder, he would go on to make the varsity boat in his sophomore year. Joe felt at home in that boat because all of the boys were Depression-era sons of dockworkers, loggers, farmers, and manual laborers. Pair that with the fact that Washington was never considered a true competitor in rowing, and it’s no surprise that expectations for the team were low.

But that crew would go on to be something special. First they beat their rivals at the University of California in Berkeley, then went on to top Harvard, Yale, Oxford, and Cambridge. And much to the surprise of the Ivy League elite, Joe’s boat beat college squads from across the country to earn a spot on the U.S. Olympic Team in the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin.

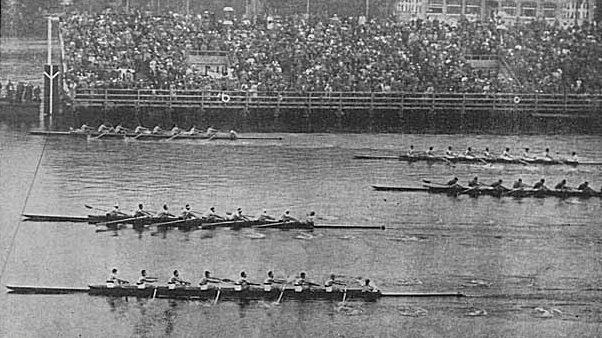

When the team lined up in front of 75,000 Olympic fans, they didn’t hear the signal and started the race in last place. Coach Ulbrickson saw this and figured that it was over. Because he knew that their strongest rower, Don Hume, had a terrible upper respiratory infection that left him struggling to stand, let alone row.

At the 2,000-meter halfway point, Joe and the team were still in last place. And now the crowd was getting so loud that Joe’s boat couldn’t hear their coxswain’s calls to increase the pace. The coxswain took his megaphone and started slamming the side of the boat so that the team could feel the rowing rhythm. They increased their pace from 32-strokes per minute to 44. The fastest ever. And as they rowed past Adolf Hitler and his top lieutenants, they showed him what is best about America. Gold by six-tenths of a second.

This story is not just about Joe and his team, it’s about the work we do.

Joe’s journey may feel nothing like ours, but there is a parallel here. And it starts with how we feel about the work we do. We know that employee engagement is low. Since Gallup started tracking the number in 2000, employee disengagement in America has hovered around 70 percent. This means that the vast majority of American workers in the last 20 years have found little fulfillment and joy in their work.

This is tragic. Because each day we spend at a job feeling stagnant and numb is a day that we wither away. A waste of our most precious resource. And one can’t help but wonder how we got here.

Of course, Gallup asks this question. In their most recent survey, they found a number of drivers for employee disengagement, including bad management, lack of professional development opportunities, micromanagement, and lack of recognition. We’ve all experienced how unpleasant these things can be, so it makes sense why Gallup sees employee disengagement as a management problem.

It also makes sense that there are now thousands of articles and books telling us the three, five, seven, or 10 things that leaders and organizations can do to improve engagement. It’s why so many organizations have launched employee recognition programs, new professional development opportunities, and more flexible and empowering work environments.

It’s all necessary and great stuff, yet here we stand. The engagement needle hasn’t moved for almost 20 years. Are we doomed to toil away the best and most vibrant years of our lives in a meaningless existence?

Something has to change.

This brings us face-to-face with a very hard question. What if our disengagement has more to do with us than the work we do? If you asked Fyodor Dostoevsky, he would likely say that it does. In 1864, he wrote a short novella called Notes From Underground. It was the fictional memoir of a retired mid-level Russian bureaucrat struggling to find meaning in his life.

Dostoevsky wrote the book as a warning for what he saw as the greatest threat to Russia. What was it? A growing obsession in America and Western Europe with the idea that every person should live to maximize their happiness and self-fulfillment. While the concept sounds wonderful on its surface, there is one big downside.

Sometimes the least fulfilled lives are those spent searching for fulfillment.

That’s because you have to do something to be fulfilled, not just think about it. Dostoevsky’s main character spent more time thinking about his life and its meaning than actually living it. So, each day devolved into a barrage of unmet expectations and an ocean of paralyzing thoughts. Existential searchers rarely find what they are looking for.

And that’s why we have to be careful with the idea of employee engagement. Unlike Joe Rantz, most of us don’t work 60 hours a week digging ditches for new roads or dangling from cliffs with a jackhammer. This is not the Great Depression. We have more job options and flexibility, which affords us a tantalizing new burden disguised as opportunity: the freedom to ask life’s biggest questions at work (e.g., Is this my passion? Am I fulfilled? Does my job matter?).

The problem is that no amount of thinking will ever give you a satisfying answer to these questions. And no employee recognition program, professional development opportunity, or manager can bring you the meaning that you seek in your work. True engagement comes from within. From disciplined action, not paralyzing thoughts. And that brings us to our biggest point.

Employee disengagement is not a crisis of management, it’s a crisis of the mind.

Don’t worry, this is not a bootstrap manifesto telling us all to suck it up and work harder because the Greatest Generation endured struggles far greater than anything we’ve seen. But it is an opportunity to reflect on what we will do with the freedom that modern work affords us.

Will we be the disengaged philosopher kings and queens in cubicles across the land perpetually questioning our own fulfillment? Or can we find joy by mastering even the most mundane tasks?

When Joe Rantz was living in that cabin in the woods, he and a friend would find scrap cedar limbs that lumber companies left behind. They would strip the bark and split the wood to make cedar shakes. It was difficult and repetitive work, but Joe soon fell in love with it. He talked about that work on his deathbed with the author Daniel James Brown. Joe described how much he loved it when the wood finally split. The spicy-sweet smell of cedar in the air and the unpredictable, yet always beautiful, patterns of orange, burgundy, and cream in the grain. Joe said that shaping cedar satisfied him down to his core, and gave him peace. Pretty good perspective for a kid whose family left him alone to live in the woods.

The engagement we seek is within.

***********